Microservices: A Technical Solution to a People Problem?

A Simple Microservice Definition

A microservice is generally defined as a small, loosely coupled, distributed service. Each service is part of a broader microservices ecosystem/architecture, comprising a set of microservices that operate together to solve a common goal. A collection of microservices can be regarded as a system.

Why use Microservices?

Microservices architectures were adopted for very specific reasons/needs such as scalability, modularity, or separation of concerns. It shifted the complexity "up the stack" by making the services themselves [potentially] simpler and easier to maintain and scale for the price of more complexity overall.

Teams were given the freedom [in some cases] to choose their own micro-architecture for each microservice. Teams wanted the freedom to be able to pick whatever language, database, and library they desired. For some, this kind of autonomy was energizing. It led to more innovation, faster development time, and shorter release cycles - for a while.

Another principle of microservices is that the team that built the service supports the service. That is a win early on as the service is being built, because support is non-existent. The team can "move fast and break things". As the service goes into production and matures, the team eventually slows down because now they must support the service and maintain it.

Challenges with Microservices

Some organizations say microservices allow them to release inter-team friction and break inertia by letting each team operate independently and keep their microservices small and elegant. This is true, but the overall architecture is quite the opposite.

Sometimes microservices exist because teams dislike code review, or overbearing ‘architects’ above them telling them what to do. While some people may realize there is nothing smart about this architecture choice for the whole system, many developers are content to care only about their team -- and not the company or application stack as a whole. For them autonomy is more important.

"Doing microservices" became validation for organizations that lack conviction, or a thesis, about how their architecture should be. This ecology of interacting parties, each acting in their own interest for the common good not only sounds utopian, but speaks to an underlying, tacit belief that the emergent mesh of services will approximate the latent natural architecture of the domain. The backlash against microservices is partly because that simply isn't true - instead microservices approximate the natural contours of the technology organization's organizational model, not the domain. This is known as "Conway's law":

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.

— Melvin E. Conway

Clearly one of the reasons why we got here as an industry is we didn’t want to (or couldn't) communicate well across teams and organizational structures. Transitioning our computer architectures from well-architected, simpler things into a complex spider web of services is not something we would do intentionally, right?

The extra complexity to operate microservices requires additional infrastructure. Kubernetes is a popular choice to orchestrate and operate all the various microservices in a system. To complete a task like booking a ride on Uber, one service must request data from potentially dozens of other services — a complex and often problem-prone process, especially as microservices scale. A service mesh becomes necessary for service discovery and securely routing requests from one service to the next. It acts like a switchboard -- it routes requests to the right service.

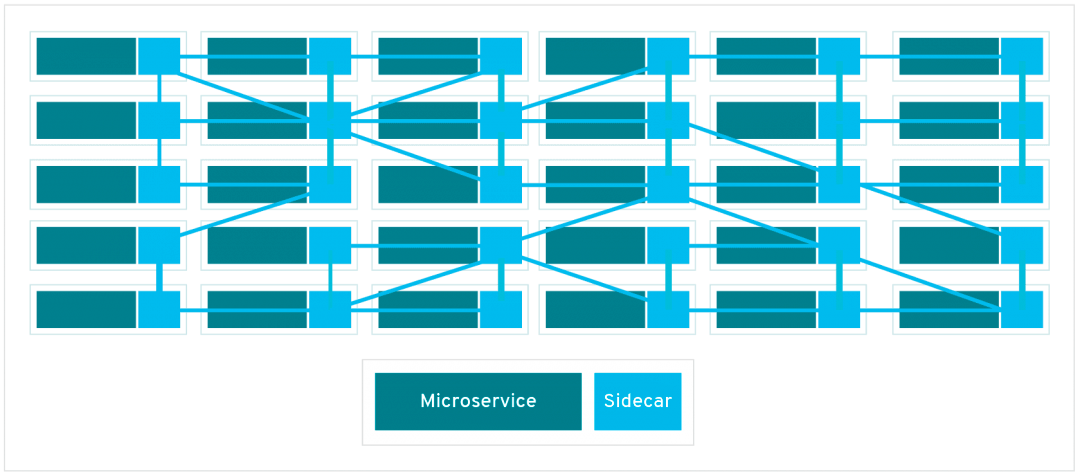

The service mesh is a dedicated, configurable infrastructure layer that can document how different parts of a microservices-base system interact. There are a couple of ways of implementing a service mesh, but most often, a sidecar proxy is applied to each microservice as a contact point. (The interactions among the sidecars put the mesh in the service mesh term.) It tends to look like this:

The Problems in More Detail

In addition to being harder to operate, microservices are more dfficult to debug. It is a lot easier to debug the interactions between components of a system when they communicate within the same process, especially when one component simply calls a method on another. This is usually just a matter of attaching a debugger to the process, stepping through the method calls and watching variables. There is no straightforward equivalent of this in microservices. Service communications are notoriously difficult to trace and piece together, requiring additional tooling, infrastructure, and complexity.

Microservices add complexity and leave us with inefficient communications, less error detection in development, easier ways to introduce errors, a worse debugging experience (e.g., relying on searching further through distributed log analysis tools), and require more and more management software to deploy.

Internal web services/APIs are often doubly inefficient by using REST (and having to convert to JSON and back) rather than binary transmissions. If multiple microservices hops are used, this all adds up and slows down the system. A conversion to JSON and back is a wasted effort, more so if done dozens of times.

“We adopted microservices so every outage could be like a murder mystery.”

Frankly, centralized architecture and standards, when put in the hands of the wrong few could be very counterproductive and feel unfair to everyone else that enjoys software design and doesn’t get to play in the sandbox. This is undeniable. However, isn’t this an argument for smaller teams and less engineering bloat, and better hiring instead?

Good architects and technical leaders can keep code maintainable and ensure it remains modular, enabling efficient future developments. These are not things we want to give up.

-

If we think about resilient systems, the most resilient systems are the ones with the least number of moving parts. The same is true for the fastest systems.

-

If we think about deployment and management and upgrades, the simplest systems to deploy and maintain also have the least number of moving parts.

Elegant Architecture Recommendations for a More Civilized Age

“Finding service boundaries is really damn hard…”

— All microservices architects, ever

Hence, it is safer to start with larger/wider boundaries - probably the boundaries of proper bounded contexts. This is especially relevant to services encompassing core business domains. Design your architecture layers properly. Organize your teams into the way you want your architectural boundaries to be. Allow for both transactions and events.

-

Web requests can be managed by one type of instance, that results in one EC2 image or whatever. Anything that can be handled within the lifecycle of one request can be handled there, and these instances are horizontally scaled behind a load balancer.

-

Asynchronous tasks are managed by a service tier, often connected to an event bus. There may be one of these for each programming language, or maybe a few more, and that would be ok. But because these are horizontally scaled and only ask for new jobs when they have free compute resources, one type of instance can contain code for any manner of asynchronous jobs.

-

Code that needs to be shared between the asynchronous services and the web tier should be kept in libraries used by both and is not a service call.

-

Don't use JSON for internal API's - consider something like Google's protobuf or Apache Thrift to serialize and deserialize data. It's fast, it's efficient, and enables much better debugging.

Benefits

-

Errors are eliminated because they can be caught better at compile time and with unit tests.

-

When changes are made, they can be made in a library, and if the API of a function changes, it is impossible to build/deploy the code until it is fixed.

-

We do not need to keep up to date with the latest in container wrangling software, and using various service discovery, ingress solutions, service meshes, or otherwise. These are problems created by complicated architectures. The service tiers can communicate over an event bus and there is no need to know the address of any server.

Image Credit: Long Distance Operators, Omaha, 1959

Switchboard operators were expected to be courteous, quick-thinking, and patient under pressure. They handled all kinds of requests, from providing the time of day to more delicate matters. Reliability engineers who manage microservices are a bit like switchboard operators -- they have to be able to understand all the connections across all the services and what happens if a connection goes down.