CoreOS: thousands of machines and millions of Docker containers... no hypervisor needed.

I have been playing around with CoreOS to get a sense of how everything works. The vision of this project is incredible.

CoreOS describes itself as "a new Linux distribution that has been re-architected to provide features needed to run modern infrastructure stacks. The strategies and architectures that influence CoreOS allow companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter to run their services at scale with high resilience."

CoreOS displaces hypervisors and machine virtualization in favor of Docker and Linux containers. CoreOS uses Linux containers to manage your services at a high level of abstraction. A single service's code and all dependencies are packaged within a container that can be run on one or many CoreOS machines.

Clustering works across platforms, meaning there is no cloud vendor lock-in. For example, CoreOS runs on Amazon EC2, Rackspace, QEMU/KVM, VMware and OpenStack and your own hardware. Running a single CoreOS cluster on multiple different clouds or cloud + bare metal is supported and encouraged. This lack of lock-in is the reason why I have supported OpenStack and CoreOS takes this even further.

We begin with concept of a large fleet of machines that start (and remain) exactly consistent at the OS level

- First, think of CoreOS somewhat like you might think of a hypervisor today. It is the first layer you put down on bare metal, or as a virtual machine in a cloud. It is a "bare minimum" Linux-based OS that supports Linux LXC containers.

- It is designed to run as a large fleet (hive?) of machines. It includes built-in primitives such as distributed locking and master election, plus key services necessary to manage the fleet of machines. (more on this later).

- It is meant to always be consistent across machines.

- CoreOS utilizes an active/passive dual-partition scheme to update the OS as a single unit instead of package by package.

- CoreOS also has the tenant of automatically updating itself. This avoids the issue of inconsistent state from machine to machine within a large cluster. Conceptually this is roughly like a self-updating hypervisor.

- Each machine has to acquire and hold a reboot lock before it is allowed to reboot. The reboot lock is held until the machine releases it after a successful update. The number of machines allowed to reboot simultaneously is configurable. The main goal to allow for an update to be applied to a fleet quickly, without impacting capacity for the services running on the cluster.

Next, we have the concept that the fleet of machines is simply a single pool of compute resources

- You treat your CoreOS cluster as if it has a single, shared init system - one giant systemd if you will.

- Instead of running a service on a specific machine, services are submitted to the cluster via the cluster manager, fleetctl, which decides where they should run.

- Your services/applications are in containers that act as small, ephemeral units that can easily migrate around a cluster of self-updating CoreOS machines.

- It is smart enough to distribute services across a cluster using machine-level affinity or anti-affinity.

- If your application consists of 5 containers fleet will guarantee that they stay running somewhere on the cluster. If a machine fails or needs to be updated, containers running on that machine will be moved to other qualified machines in the cluster.

... with a single, shared brain

- CoreOS provides a distributed key value store called "etcd".

- The etcd client runs on each machine in a cluster. etcd gracefully handles master election during network partitions and the loss of the current master.

- Docker containers can read, write and listen to etcd over the docker0 network interface. With these three actions you construct extremely sophisticated orchestration to happen whenever etcd values change. An example of this would be listening for changes and then to reconfigure an upstream proxy when a new container of an application is started.

- Since etcd is replicated, all changes are reflected across the entire cluster. Your application can always reach the local etcd instance at 127.0.0.1:4001.

- Your applications can read and write data into etcd. Common examples are storing database connection details, cache settings, feature flags, and more. Let's say we're running a simple web app like Wordpress. Instead of hardcoding our database address with in the config file, we'll fetch it from etcd instead. It's as simple as curl-ing http://127.0.0.1:4001/v1/keys/database and using the response within your DB connection code.

Summary

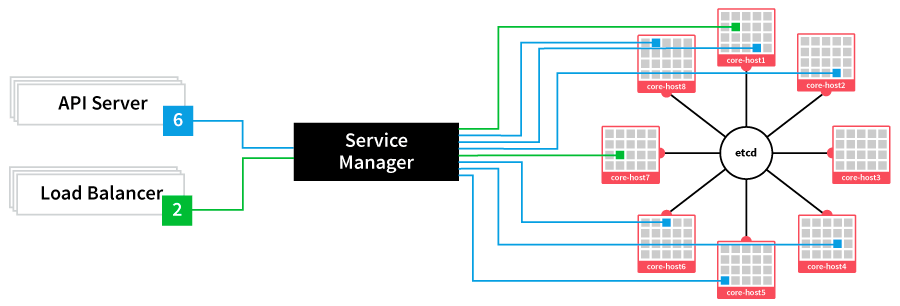

So now we have a hive of self-updating Linux hosts with a single, distributed init system (systemd and fleet) and a single shared brain (etcd). It looks something like this:

This depicts eight containers (two load balancers and six api servers) being managed by "fleet" to run in various CoreOS hosts in the cluster, with shared access to etcd.

Momentum is shifting this way rapidly. Earlier this month Rackspace announced OnMetal. Rackspace's OnMetal Cloud Service is the first of its kind. Using OnMetal you create machine instances using OpenStack APIs but, instead of being provisioned a virtual machine, you are provisioned on physical hardware. OnMetal servers are single-tenant, bare-metal servers provisioned via the OpenStack API and can be spun up as quickly as VMs.

Once OnMetal is live, you'll be able to provision CoreOS instances on Rackspace's OnMetalcloud. This combination gives you the ease of spinning up machines with the click of a mouse, the security of running CoreOS with automatic updates, and the raw horsepower of running on bare metal. Pretty impressive!